Welcome back. Hope you enjoyed The Comparison of the Subjunctive Mood in English and in Spanish (Part 1). Let’s continue!

2-5. The Subjunctive Use Cases in the Future Context in the Unrealistic Scenario (English Only)

As you may have noticed, when explaining the impossible hypothesis, we group the cases in the present with those in the past. Because from the perspective of grammar, the conjugations are only different when the context is in the past, while there are no differences for situations in the present and in the future.

This is easy to understand intuitively: our impossible hypothesis for now implies that it will stand in the future, and its result will affect both the present and the upcoming; while usually we won’t bring the impossible hypothesis of the past to the current situation, even one hypothesis not possible before can be already viable right now.

Actually, there exists the future subjunctive in Spanish, but because of its inconvenience to use, it is rarely mentioned in the modern Spanish. Therefore, in this language, we apply the present subjunctive to the future scenarios.

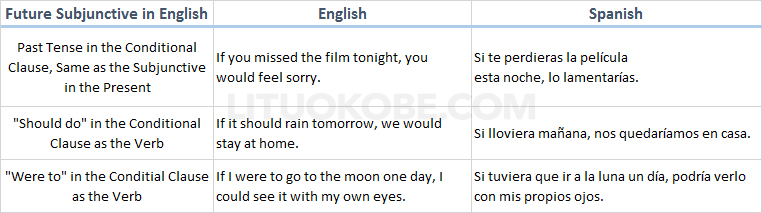

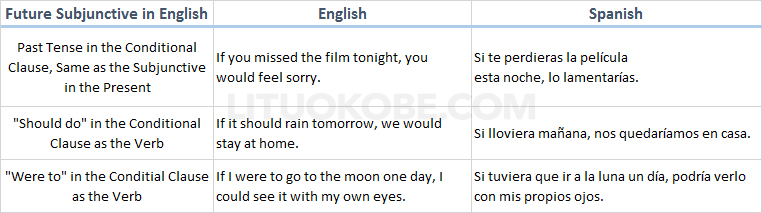

But the English language still keeps certain mechanism for future subjunctive. As we discussed in previous chapters, there is no dedicated subjunctive conjugations in English, as a result, the future subjunctive form is achieved with verbs conjugated in certain tenses. We can also see how fragmented the ways to use the English subjectivity.

Here are some examples:

2-6. Variation of Inversion in the Unrealistic Scenario (English Only)

The inversion only exists in the subjunctive in English, which makes the usage of the mood in the language more scattered: when either “were”, or “had”, or “should” shows up in the conditional clause, you can use the word to replace “if”.

For example:

Were I to go to the moon one day, I would see it with my own eyes.

Were it not for his help, I wouldn’t go home now.

Had the doctor come last night, the boy would have been saved.

Hadn’t it been for the determined captain, all the passengers on the board wouldn’t have been saved.

Should it rain tomorrow, we would stay at home.

3. Subjective Scenario

3-1. The General Case of the Subjective Scenario

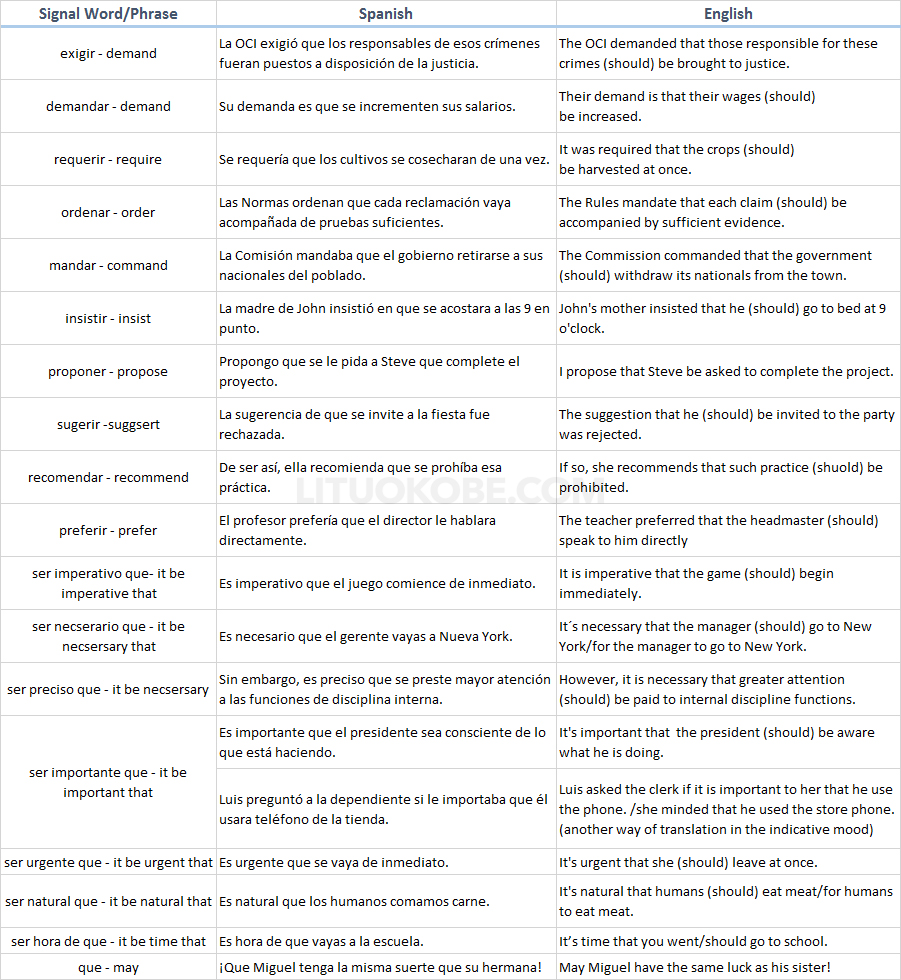

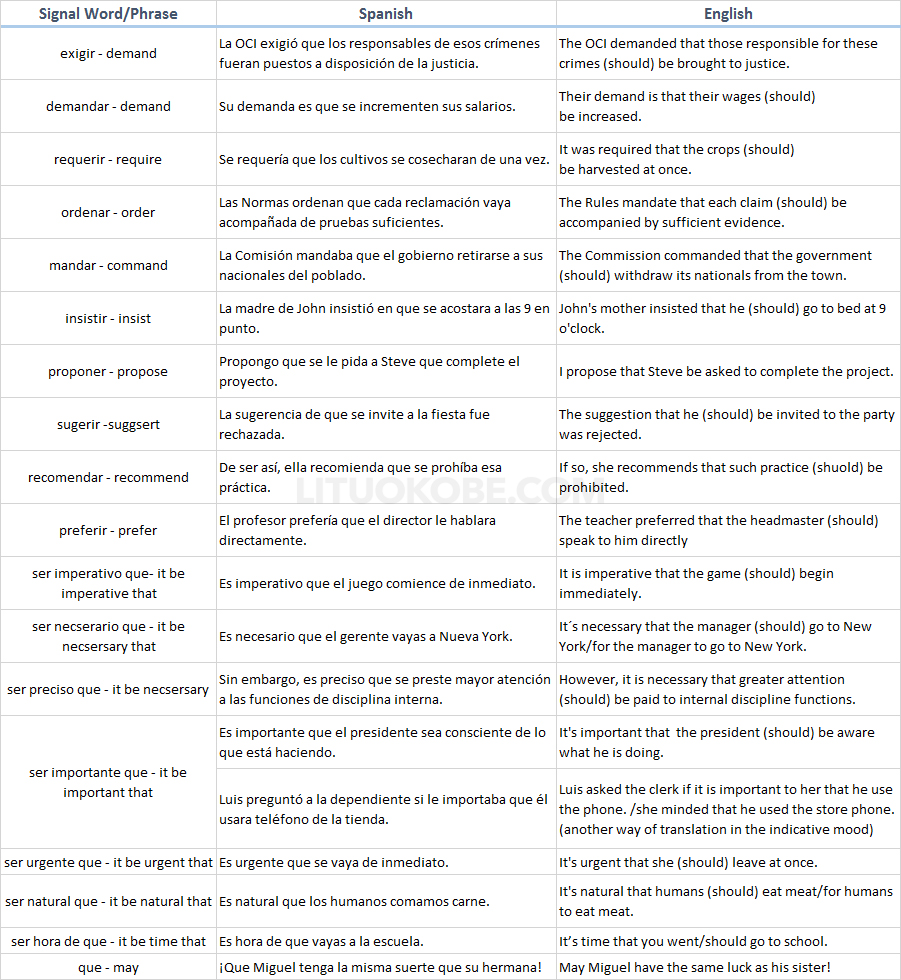

In this scenario, the speaker is making a comment emotionally subjective, such as the content in the object clauses of verbs like “require”, “order”, “insist”, “suggest”, “prefer”, “prohibit”, “permit” or “warn”.

Besides in these object clauses, in some subject clauses the subjunctive mood is also required. In Spanish and English, we usually use an adjective to describe an event which needs to be explained in a sentence with certain length. As a result, we usually make the sentence a subjective clause led by “que”/“that”, located at the second half of the whole sentence which starts with “Ser/Estar”/“It be” and the adjective as an redicative.

The subject clause should be in subjunctive when the adjective is “necessary”, “important”, “urgent”, “natural”, etc. As we can see, these adjectives usually imply a strong emotion (with “natural” as an exception).

What’s more, blessings initiated with “Que”/ “May” are designed for the subjunctive mood, most of the time in oral communication.

In terms of the way to realize the subjunctive in this scenario, we can directly use the corresponding verb conjugations in Spanish (present subjunctive, present perfect subjunctive, past imperfect subjunctive, past perfect subjunctive), which is very straightforward and easy to understand.

Nonetheless, there emerge new key points in English: despite the tense of the principal clause, we need to use “should do sth” or “do sth” (the infinitive form of verbs); but when the signal phrase is “it’s time that”, either “should do sth” or the past tense is needed. This use case is totally different from the past tense as subjunctive and the past perfect tense as subjunctive which we use in the unrealistic scenario, and there is no connection at all. Consequently, for beginners, it’s actually not as memorization friendly as the separate subjunctive conjugations in Spanish.

Let’s check some examples of the subjective scenario:

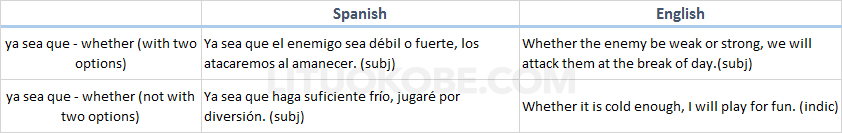

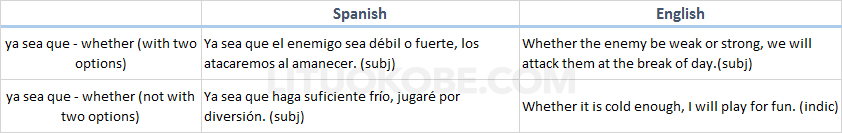

3-2. Key Point in the Subjective Scenario: “Ya Sea Que”/ “Whether”

When expressing a concept like “whether”, actually, we need to use the subjunctive mood in both Spanish and English.

But as mentioned previously, this mood is employed less and less in English so that what comes after “whether” is usually the indicative. Here, we are going to take a more common approach right now: when “whether” shows up in English and there are two options available, we use the subjunctive (verbs in the infinitive form); when there are more than or less than two options, we employ the indicative.

While in Spanish, so long as “ya sea que” appears, we always use the subjunctive.

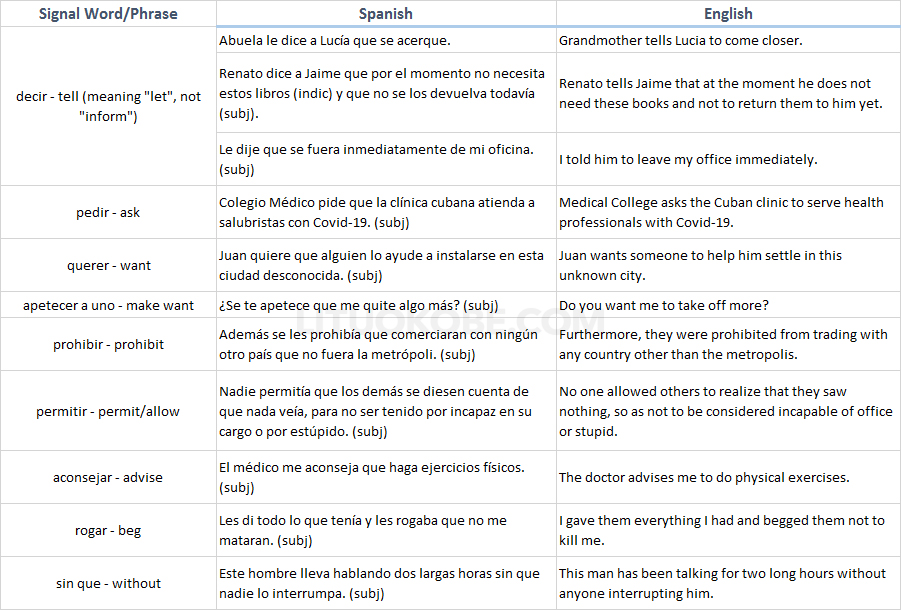

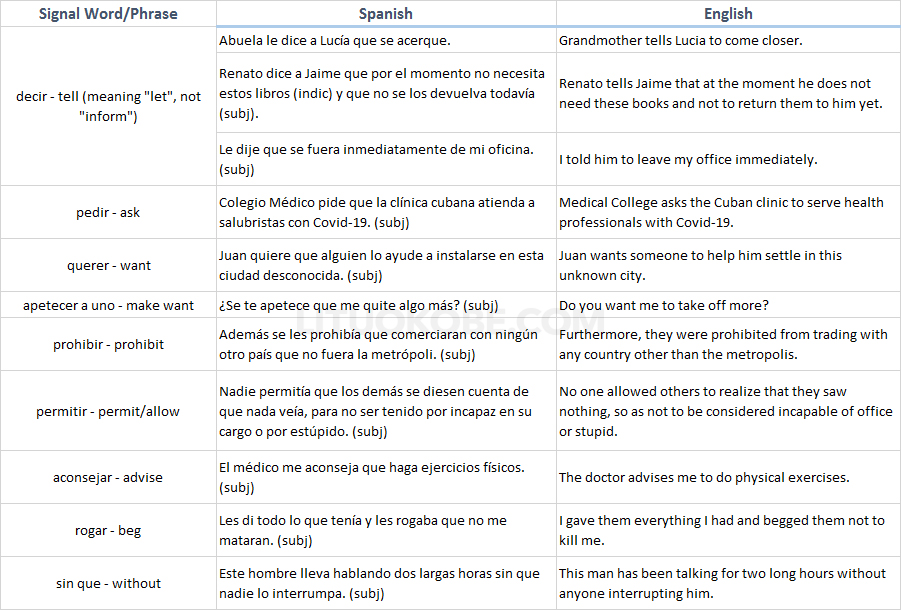

3-3. Key Point in the Subjective Scenario: Expressions of Prepositional Phrases and Noun Phrases to Replace the Clause in English

Sometimes, when it comes to the content that is expressed with an emotionally subjective verb, it is preferred to use a subjunctive clause in Spanish, whereas in English, prepositional phrases are employed to replace the clause. If we use the clause in English, theoretically it should be subjunctive as well, but this is not in accord with the best practice in the language. The subjunctive clause in Spanish is more common than that in English in terms of using habit. This kind of verbs usually mean “ask”, “want”, “prohibit”, “advice”, etc., and they are barely followed by a clause when used.

(Actually, in the examples of the subject clauses, there are several similar cases. For the sake of convenience, I adapt several English sentences with prepositional phrases to those with subjunctive clause, although they become a bit awkward.)

Moreover, “sin que” in Spanish matches “without” in English, indicating something that has not happened. Technically speaking, the subjunctive mood should be prepared for the phrase in both languages. But in English, it is more natural to put “without” in font of a noun or a noun phrase at most, which means there will not be any clause here, consequently no subjunctive.

Please see the examples when a subjunctive clause is used in Spanish but an expression of prepositional/noun phrase in English in the subjective scenario:

4. Subjunctive for Spanish, Indicative for English

In practice, the definition of “the subjective state of which it’s meaningless to tell true or false” is so much broader in Spanish than that in English that the subjective mood is demanded so long as the meaning of a word’s clause shifts a little bit from the reality. This kind of words can be, for example, “maybe”, some phrases related to emotions like “hope”, “be happy”, “fear”, “be surprised”, “doubt” and “be sorry”, and some that express negative opinions such as “not think”, “deny” and “not believe”. This detached use of moods even applies to the adverbial clause of time in the future and the attributive clause that describes a noun uncertain. In all the situations mentioned above, we can just use the indicative mood in English. In other words, the Spanish grammar has much more exacting requirements to use the indicative than its English counterpart and only allows the existence of this mood in a highly realistic scenario.

(Actually, some content that is expressed with an emotion related word also required subjunctive mood in the ancient English. But because this language is becoming more analytical today, we hardly find anyone doing this anymore. Yet please do not feel strange if you do.)

I classify the situation into two categories to make things easier:

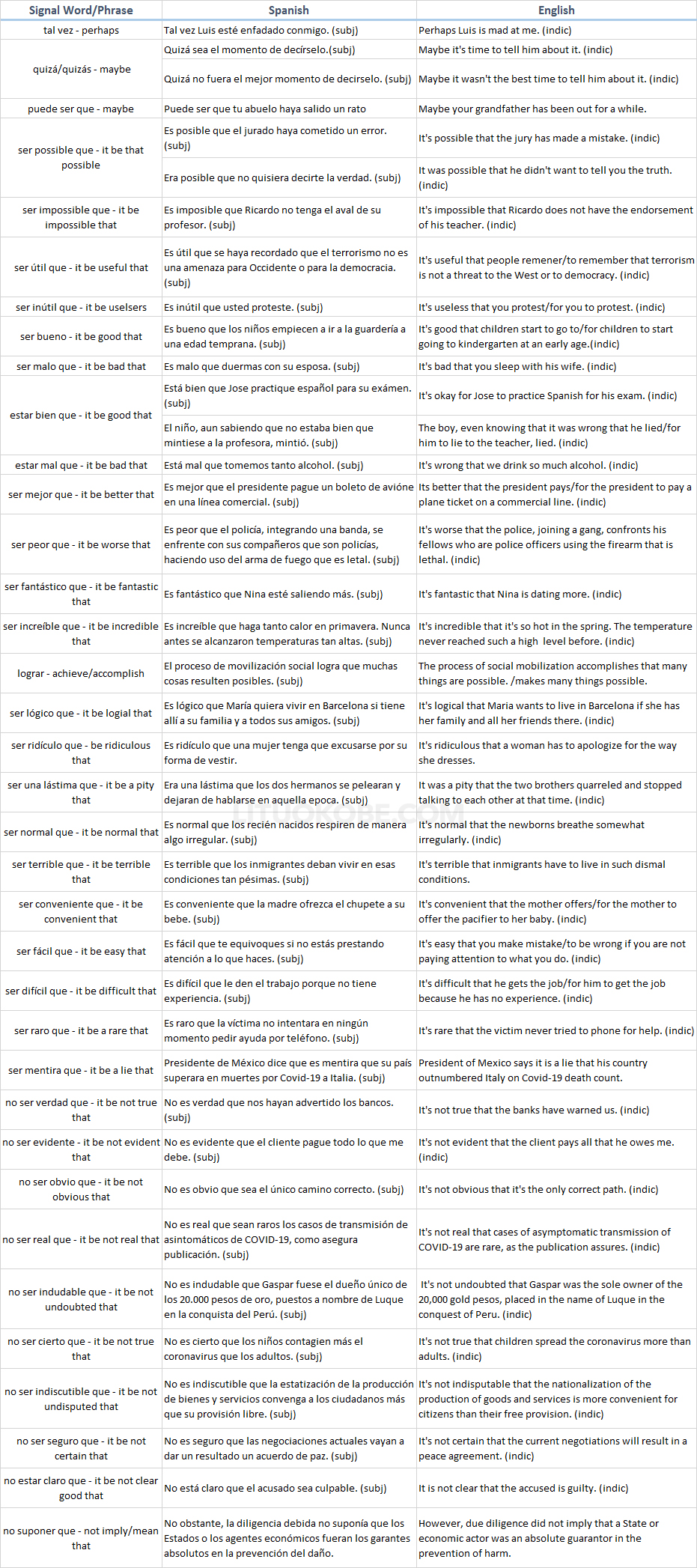

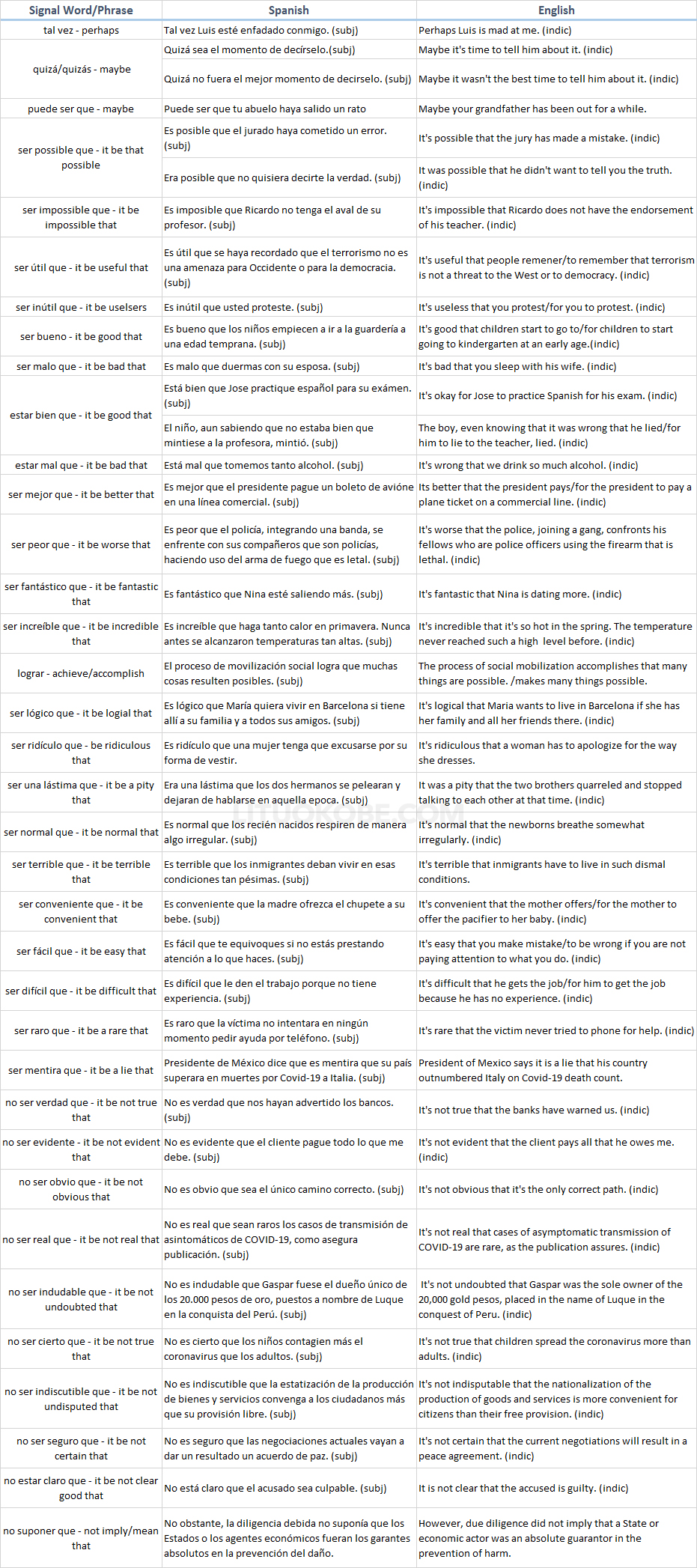

4-1. Subjunctive for Spanish, Indicative for English – Signal Word/Phrase

When some words meaning “maybe” show up, the sentence is usually subjunctive in Spanish, but indicative in English. We can understand it as a grey area of definition: in Spanish, it is worthless to decide whether it is true or not for something that “maybe” happens, whereas in English, it is meaningful.

It is worth mentioning that there does exist one “maybe” for the indicative in Spanish: “a lo mejor”. Its usage almost exactly matches that of “perhaps” in English. We can safely draw the conclusion that the Spanish grammar is quite integrated: when explaining “something maybe happens”, if you are more decisive and rather confident to tell true or false of the statement, use “a lo mejor” and the indicative; if you are hesitant and reluctant to be strict with the authenticity, employ words like “tal vez”, “quizá/quizás”, or “puede ser que” together with the subjunctive.

“Ojalá” as discussed before is usually ahead of the past subjunctives in the unrealistic scenario, and its equivalent in English “wish” also signals subjunctivity in the scenario; but when the Spanish word is used with the present subjunctive, it only means a regular “hope” and its English counterpart now should be “hopefully” which is always accompanied by the indicative mood. Based on this logic, any verb that expresses a normal expectation, such as “esperar”/ “hope”, will lead an object clause whose content is meaningless for authenticity check in Spanish, but the other way around in English. Again, we can feel the broadness of the subjunctive definition and the strictness of the indicative definition in Spanish.

Besides, many subject clauses which start with “ser/estar”/ “it be” with an adjective also need to be subjunctive in Spanish and indicative in English, and the adjectives usually describe emotions, or express confirmation yet the sentence is negated by words like “no”/ “not”. Generally speaking, subjective clauses like this tend to be subjunctive in Spanish and indicative in English in more cases, while it’s actually less common to find an adjective that requires the subjunctive mood in the clause in both languages.

These use cases can be regarded as an extension of the subjective scenario in Spanish. But in English, the extension is absent.

Meanwhile, as the application of the subjunctive mood is too broad in Spanish and the mood is a must-have for many signal words, we need to add modal verbs like “would”, “could”, “might”, or “should” to clarify certain attitudes and emotions when translating the Spanish subjunctive sentences into English. In fact, a big part of the simplification of the subjunctive mood in English is about turning the verb under the mood into the infinitive form after a modal verb. This will be mentioned in the following examples.

Thanks for reading. The article continues on The Comparison of the Subjunctive Mood in English and in Spanish (Part 3).